By Victoria Stone-Meadows

Women armed with a university degree in the South-East are at a severe disadvantage in finding full-time employment compared to men in the region.

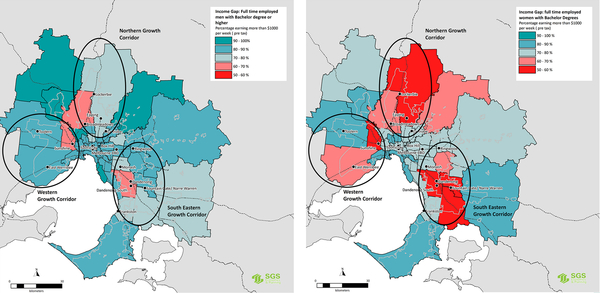

The data used for the research focused on tertiary-educated people in full-time employment, and showed that women in Melbourne’s growth areas were both paid less and have less full-time employment than men.

The preliminary research undertaken by planning and economics firm SGS Economics and Planning was released on International Women’s Day Wednesday 8 March.

Senior Consultant for SGS Lucinda Pike said the research came about when the firm realised there was a gap to fill in productivity data.

“We were discussing International Women’s Day in the office, and we do a lot of work on productivity, and we have found there is not much data looking at the gender gap and difference in productivity,” Ms Pike said.

“We have this sense of how it works across the board, but there is very little that looks at the difference between genders.”

What the researchers found was that women in growth areas are much more adversely affected by being further away from the knowledge centres of the city and inner suburbs.

Only 55 – 65 per cent of tertiary-educated women were working full time, earning over $1000 per week in Casey, compared to 78-85 per cent of their male counterparts.

“This is a very significant difference between men and women earning a thousand dollars a week,” Ms Pike said.

“While we are only looking at the broad overview of tertiary educated and full time employed people, it is a staggering difference.”

“We were surprised by this and how it is particularly pronounced in the growth corridors and outer parts of Melbourne.”

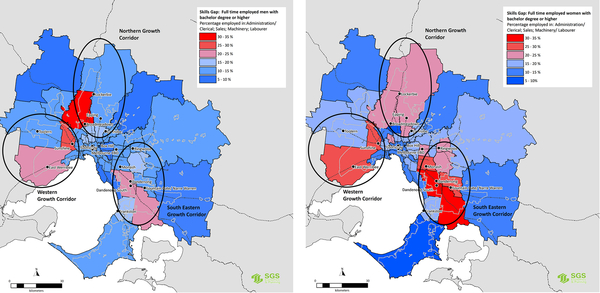

The gap between the genders in the South-East Region doesn’t only affect income with jobs requiring a university degree being disproportionately being held by men.

Over 30 per cent of women who had a university degree in both Casey and Dandenong were working in jobs that did not require that level of education.

“Women are able to work in jobs that require the education but are not being employed in those roles in growth areas,” Ms Pike said.

Ms Pike said the consequences affect the wider community and not just those with a university degree looking for work and can further entrench employment inequality for women.

“One of the things we observe is when you have tertiary educated women and they are employed in a position that doesn’t need that education; there is a flow on effect,” she said.

“It affects others that would be applying for those jobs, then they have to take a job that is less secure, with less pay.”

There are many factors that contribute to the gap in job access and income for men and women in the Casey and surrounding regions, but Ms Pike said there were a few things that made a big difference.

“A big part of it is about knowledge intensive industries not being in those areas,” she said.

“A more diverse array employment opportunity would definitely help.”

“When we talk about this, we have to talk about having access to those jobs through public transport.”

“If it only takes you half an hour to travel to the CBD when there are no jobs locally, there are no issues, but in these growth areas the travel time is really substantial trying to get to the knowledge clusters.”

SGS will continue to analyse employment data to get a greater understanding of productivity in Melbourne growth areas in the coming months.