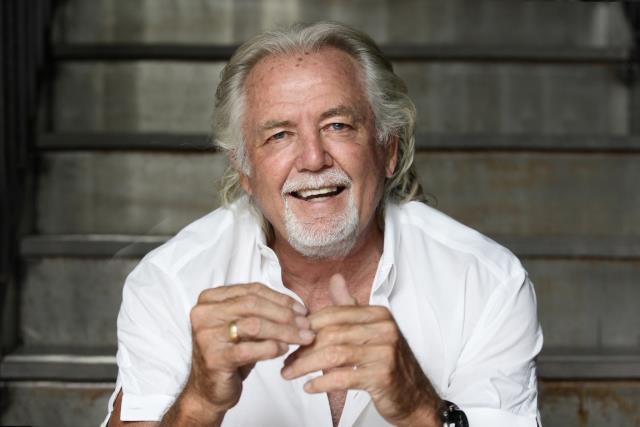

Property developer John Woodman has lost his latest Supreme Court bid to prevent the public release of an Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) report into alleged corruption in City of Casey planning matters.

The court resolution paves the way for the long-awaited tabling of the Operation Sandon report in State Parliament, which is expected to happen sometime later this year.

Mr Woodman was publicly examined in November 2019 as part of IBAC Operation Sandon hearings into Casey councillors, ALP politicians and Mr Woodman and his business associates.

In his decision released on Thursday 1 June, Justice Steven Moore declared the proceeding for an ‘interim’ injunction be dismissed, stating Mr Woodman had “failed to establish a prima facie case” in relation to his claims.

According to Justice Moore’s decision, Mr Woodman commenced another proceeding in the Supreme Court of Victoria against IBAC in March of 2022, in which he sought to prevent publication of the report on Operation Sandon on the ground of denial of procedural fairness.

In November 2022, Justice Timothy Ginnane found that, before publishing the report, IBAC should disclose a limited number of additional documents to Mr Woodman for his response.

On Friday 20 January this year, Mr Woodman provided IBAC with his response to the draft report in relation to Operation Sandon and the further documents.

On or about Sunday 14 May, Mr Woodman became aware of media reports that the delivery of IBAC’s report to Parliament in relation to Operation Sandon was imminent.

He filed a summons seeking an ‘interim’ injunction on Thursday 18 May, which aimed to restrain the publication of IBAC’s report on the basis that its tabling in Parliament would result in him suffering “catastrophic and irreparable damage”.

Mr Woodman also sought orders that IBAC provide him with certain information.

According to a writ filed on Thursday 18 May, Mr Woodman sought final declaratory relief that IBAC breached a section of the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011 and denied him procedural fairness by holding his examination in public, as well as a perpetual injunction restraining IBAC’s publication of its report and damages.

According to section 117 of the Act, an examination is not open to the public unless the IBAC considers on reasonable grounds that there are exceptional circumstances, it is in the public interest to hold a public examination and a public examination can be held without causing unreasonable damage to a person’s reputation, safety or wellbeing.

As such, Mr Woodman put forward that IBAC breached a duty of care which it owed him by publicly examining him, thereby causing him reputational damage and economic loss.

However, in his decision, Justice Moore said IBAC’s responsibility was not to uphold a duty of care.

“IBAC’s principal statutory function is to identify, expose and investigate corrupt conduct,” he said.

“The due performance of that function may inevitably cause reputational damage and economic loss to persons under investigation.

“I do not consider that Mr Woodman has a prima facie case in relation to any of his claims advanced in this proceeding.”

Justice Moore said Mr Woodman’s delay in raising his claims in this proceeding and not during the March 2022 proceeding was “egregious and unexplained”.

During the public examinations, Mr Woodman’s representatives made no application to cross-examine any witnesses.

IBAC refused to comment on the Supreme Court case.