The names and histories of many of Australia’s First Nations soldiers remain shrouded in mystery – but one Cranbourne resident has made it his mission to uncover their stories.

Peter Bakker, an amateur historian and military researcher of 16 years, has spent thousands of hours researching and verifying Aboriginal participation in Australia’s early military forces.

His work has dispelled many of the myths around their service and treatment, while also uncovering the names of some Australia’s earliest Aboriginal soldiers.

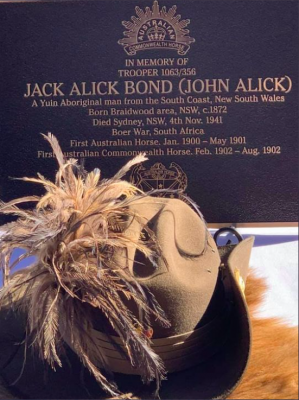

One of those soldiers is Jack Alick Bond.

Jack was born around 1872 in the Braidwood district of New South Wales, the son of Jacky Alick and Ellen de Mestre. His maternal grandfather was the trainer of Archer, the winner of the first and second Melbourne Cups. His father was a police tracker, as was his paternal grandfather, the tribal spokesperson ‘King John Bond’.

Jack was a member of the Yuin Nation living near Braidwood, on the south coast of New South Wales.

He served as a police tracker before enlisting in the Boer War, making him one of only ten currently known Aboriginal soldiers to serve in this war.

Jack served as a fully-fledged trooper as part of the 1st Australian Horse, a colonial NSW militia, as well as the 1st Australian Commonwealth Horse. His horsemanship, skill with a rifle and bush skills were recognised for their usefulness by the army.

The 1st Australian Horse unit underwent comprehensive training, including how to shoot while riding on horseback and charging with the use of sabres. Jack passed the tests for selection to serve overseas just two weeks before his ship left for South Africa.

Mr Bakker said that it was a “credit to the army selectors that he was chosen based on his skills rather than eliminated because of his Aboriginality.”

On 17 January 1900, Jack set sail on the ‘Surrey’ for South Africa, arriving in Cape Town on 23 February 1900. His first major battle was at Poplar Grove in March 1900.

The war was tough, with soldiers having to survive harsh conditions including meagre rations, traversing rough Veldt country, poor hygiene and spending many cold nights exposed out in the open.

While convalescing from a bout of the deadly enteric fever in September 1900, Jack sent a letter back home to his white friend, George Larkin, stating that he was fed up with the war – saying that it had “lasted quite long enough” and that he was ready to go back to Australia.

When the letter was discovered by Mr Bakker in late 2013, it was the earliest known correspondence from an Australian Aboriginal serving overseas. In 2020 Bakker located two letters by another NSW Aboriginal soldier, Frank Leighton Sinclair, that predated Jack’s letter by a few months.

Mr Bakker said Jack’s letter and life story challenge the widely-held generalisation that First Nations people were not accepted by all white Australians in colonial Australia.

Jack returned to Australia on 2 May 1901 and was welcomed back to Braidwood with a wine and cigar night in the local Albion Hall and hosted by the Braidwood Mayor, Alderman Higgins.

In 1901 the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York undertook a royal tour of British dominions that included their participation in opening Australia’s first Federal Parliament in Melbourne on 9 May 1901.

On 1 June 1901 in the grounds of Government House, Sydney, the Duke presented nearly 1000 returned Boer War veterans, including Jack Alick Bond, with the Queen’s South Africa Medal. Jack personally received his medal from the hands of the future King George V of England.

in 1902 Jack returned to South Africa for a second tour of duty and late in 1918 attempted to enlist to serve in World War One. By 1918, he was around 44 years old, although he stated his age as 38 years and 11 months. It’s unclear whether his application was fully processed.

Jack died on 4 November 1941 after being run over by a tram on Anzac Parade in La Perouse, Sydney.

A newspaper report from the time notes that he was well-known in the area as a seller of curios and boomerang exhibitor at La Perouse.

While there was a short funeral notice placed in the newspaper, no record has yet been found describing his funeral.

However, his story did not end there.

After uncovering Jack’s history, Mr Bakker – who was also instrumental in the creation of Victoria’s first Aboriginal War Memorial in Warrnambool – contacted some of Jack’s family descendants.

While Jack has no direct descendants there are many Bond and Ahoy descendants via his brothers, half-brother and two half-sisters.

In 2014 Mr Bakker located Jack’s unmarked grave in Botany Cemetery Eastern Suburbs Memorial Park in Sydney.

With no commemoration of Jack’s life and military service existing, Mr Bakker formed the Jack Alick Bond Memorial Grave Committee in mid-2020, which began planning for a grave memorial and re-dedication ceremony for Jack.

Having raised sufficient funds, including a grant of $30,000 from the NIAA (National Indigenous Australians Agency), Monday 30 May – on the 119th anniversary of the Treaty of Vereeniging which ended the Boer War – saw the memorial and re-dedication service of Jack’s new grave and plaque.

The service was attended by many Bond and Ahoy family descendants, including Linno Ahoy Thomas, who provided guidance on incorporating Aboriginal culture into the event.

The service began with a smoking ceremony and featured traditional Aboriginal dances.

Thanks to historian Mr Bakker’s research and the publication of his illustrated booklet, ‘Recognising a Warrior: The extraordinary life, family and military service of an Aboriginal man – Jack Alick Bond’, Jack’s story is now known and preserved.

Mr Bakker continues his mission to uncover the lives of other early Indigenous soldiers, painstakingly tracing their family trees and service records for verification, before presenting them in a dossier to the Australian War Memorial for formal recognition.

“There is still more Aboriginal history to be found and acknowledged,” Mr Bakker said.