A major scientific breakthrough has opened new conservation pathways for two critically endangered Australian native orchids, after researchers at Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria identified the fungal partners essential to their survival.

Newly published research led by Dr Noushka Reiter, in collaboration with Richard Dimon as part of the Cranbourne garden’s Orchid Conservation Program, has identified the specific mycorrhizal fungi required for the successful germination and growth of two critically endangered native orchids (midge-orchids), Corunastylis insignis and Corunastylis branwhiteorum.

All orchids depend on symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi to germinate in the wild.

Until now, however, the fungal partners essential to the Corunastylis genus, which has more than 25 species, were unknown, severely limiting conservation efforts.

“This research fills a critical knowledge gap,” professor David Cantrill, chief botanist of Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, said.

“Without understanding the fungi these orchids depend on, it has been extremely difficult to propagate them successfully for conservation. We can now do that with confidence.”

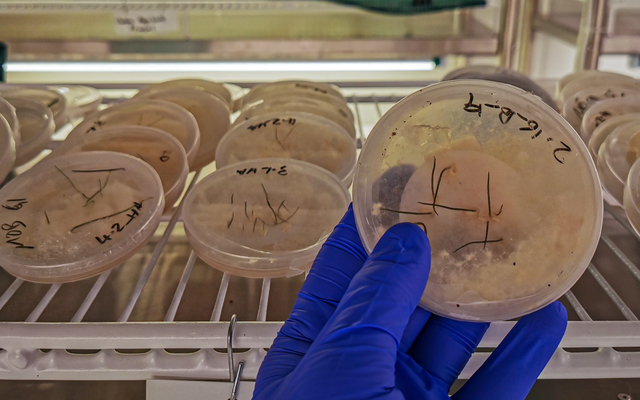

The research team isolated fungi from orchid roots collected at multiple sites and analysed their genetic identity. They found that both endangered species form associations with fungi from the Rhizoctonia group (family Ceratobasidiaceae).

Corunastylis insignis was associated with two fungal species, while Corunastylis branwhiteorum relied on a single species.

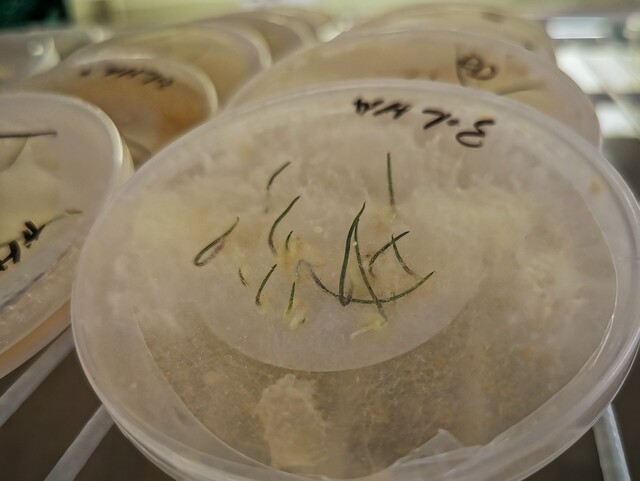

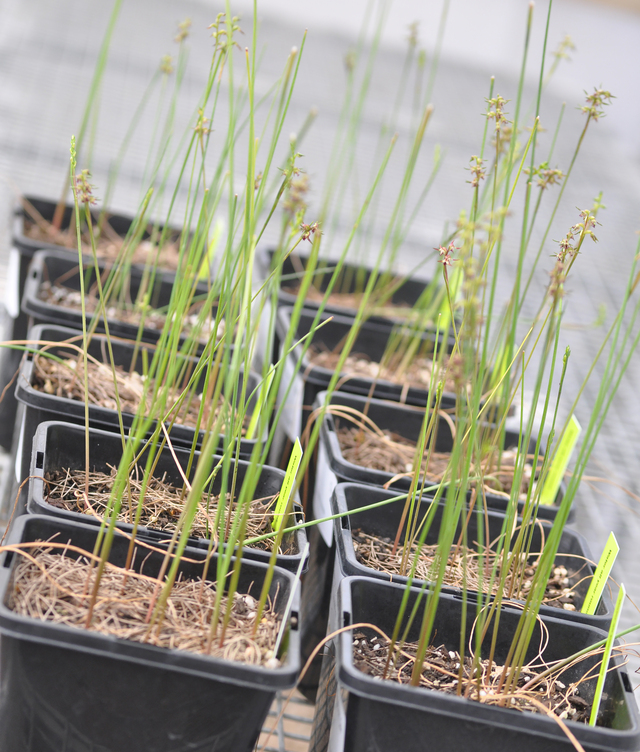

The scientists demonstrated that both orchids can be reliably grown from seed to adult plants using these fungi under symbiotic conditions.

One growth medium, Modified Oatmeal Agar, resulted in significantly higher germination rates than the alternatives tested.

“Our results show that symbiotic propagation of these orchids is not only possible, but highly effective,” professor Cantrill said.

“This significantly improves the outlook for reintroduction and long-term survival in the wild.”

The study also revealed variation in germination success between different fungal isolates of the same species, highlighting the importance of maintaining fungal diversity in conservation programs.

To maximise resilience and adaptability, the researchers recommend using a range of fungal isolates when propagating orchids for translocation, ensuring plants have the best chance of thriving across different soil and environmental conditions.

The Orchid Conservation Program, based at Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne, is a nationally significant initiative dedicated to the protection, propagation and recovery of threatened orchids.

The program integrates scientific research, seed banking, symbiotic propagation and reintroduction to secure these species for the future.

Australia is home to an estimated 1,800 species of terrestrial orchids, many of which persist in critically low numbers due to habitat loss.

Without targeted conservation action, many of these small, isolated populations face extinction.

The Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria Orchid Conservation Program is currently growing more than 230 species of threatened Australian terrestrial orchids and, in partnership with collaborators, has reintroduced orchids to more than 50 sites, resulting in measurable population recovery and self-sustaining wild populations.

“There are many native orchids at immediate risk of extinction if we don’t continue this critical work,” professor Cantrill said.

“But our conservation facility is now at capacity. To scale up conservation science, safeguard more threatened plants, and support collaborative research, we need to expand our facilities to protect Victoria’s extraordinary biodiversity for generations to come.”

This work was supported by volunteers, grants and funding from the NSW Government’s Saving our Species (SoS) Program, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

The paper can be read here: doi.org/10.1071/BT25058