In an interview with the Pakenham-Berwick Gazette in 2001, jockey Peter Mertens said he hoped one of his six children would follow him into the saddle.

The distressed state of the rocking horse on the front porch of his Cranbourne South home that day suggested at least some of them had shown an interest.

Beau, only three at the time, would be the one to step up. He rode Golden Path to victory in the Silver Bowl Series Final at Flemington last Saturday, 1 July – but sadly Dad wasn’t there to see it.

Peter Mertens had succumbed to a battle with pancreatic cancer the previous Saturday, aged 58, sparking an outpouring of emotion from the close-knit racing community.

Beginning his riding career in 1979, Peter Mertens rode over 2100 winners, including seven Group 1s in Victoria and South Australia.

His first Group 1 win came in 1999 aboard Rustic Dream in the Futurity Stakes at Caulfield. He also enjoyed great success with Bart Cummings’ stayer Sirmione, whom he rode to win a Mackinnon Stakes in 2007 and an Australian Cup in 2008. His final Group 1 was the 2012 Australasian Oaks with Invest.

Mertens also won five Group 2 and 16 Group 3 races. After retiring from riding in 2014 following a serious fall in late 2013, he joined the training ranks and saddled up his first runner when Monteegar ran at Geelong in September 2017.

He was also proud of the fact that he was one of only two jockeys – along with Harry White – to win the Wangoom Handicap and Warrnambool Cup double at the famous May carnival, one of his favourite racing places, outside his ‘home turf’ of Gippsland. He achieved that feat in 2005 aboard Mccarthy’s Bar and True Coarser.

Mertens is survived by wife Gulcin, his six children and three stepchildren.

“The Victorian racing industry is deeply saddened to hear of the loss of Peter Mertens after a brave battle with illness,” Racing Victoria chief executive Andrew Jones said last week.

“Peter was an outstanding jockey across 35 years in the saddle and was a well-respected member of an industry to which he contributed so much.

“We extend our sincere condolences to Peter’s family and friends in the knowledge that the Mertens name will live on in Victorian racing through his son Beau.”

Victorian Jockeys Association chief executive Matt Hyland also expressed his sympathies to the Mertens family.

“We are incredibly sorry to hear of Peter’s passing and extend our condolences to his family – in particular his son Beau. We are thinking of them all at this particularly sad time.

“Peter was as gallant in fighting his illness as he was on the racecourse, and he will be sorely missed by many people in Victorian racing and beyond.”

That 2001 Gazette article began with an anecdote about the 1995 Sale Cup – or more accurately the venom-charged aftermath in the jockeys’ room.

Glamour jockey Damien Oliver had made the trip to partner the Jim Houlahan-trained Unsolved, which was sent out a warm favourite, due largely to Oliver’s presence.

But Mertens, the former local apprentice, wasn’t impressed an on the way to the barriers made it crystal clear that Oliver was trespassing.

“The give way signs at Flemington might say D. Oliver, but here they say P. Mertens,” he told the visiting hoop.

As it transpired, Mertens won the race on the John Maloney-trained Top Walk in a blanket finish, with Unsolved rattling home for an unlucky third.

Oliver quickly fired in a protest, which was thrown out by the stewards after a long deliberation and the champion jockey was heard to voice his displeasure at the decision upon leaving the stewards room. The outburst made headlines the following day.

Not that it matters; the local boy had won the day.

“The record books show P. Mertens won the Sale Cup,” Mertens said, recalling the event. “Not that D. Oliver was a bit stiff.”

That story says a lot of P. Mertens, who had to endure many ups and downs in his career, including a readjustment of attitude after a two year sabbatical and recovering from a life-threatening fall at Pakenham.

At the time of the Sale Cup run-in, Mertens says he still carried the ‘country jockey’ tag, but by the early 2000s was establishing himself among the elite jockeys.

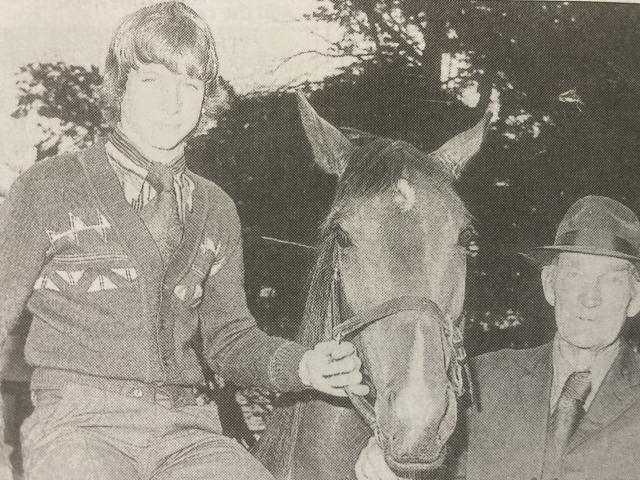

Yet he insisted he was still a country boy at heart and would not have made it at all if not for his upbringing as an apprentice to the legendary Sale trainer George O’Mealy.

“He was a tough old bastard, no doubt about that,” Mertens recalled in the 2001 article. “But I don’t think I’d be here today without that tough, hard start he gave me. My outlook comes from those first three years with George.”

Mertens considered himself lucky to have been taught in the old school, where he had to get himself out of bed at 4.30am every day and have the horses watered and fed and the boxes mucked out by breakfast. It wasn’t only racehorses at the O’Mealy stable; there were the stallions and broodmares as well.

After breakfast the horses had to be worked, either on a grass track on the property or at the racetrack for fast work. The apprentice was also expected to dress the horse before trackwork – brushing the mane and tail and tending to the hooves.

“The day didn’t really finish until 7.30 at night. There was one year when I only had two days off.”

George was 73 when Mertens joined the stable and didn’t drive beyond Traralgon or Bairnsdale, which meant the young jockey had to rely upon lifts or public transport to get to the races.

Mertens remembered using trains and taxis to get to Melbourne for one of his early city rides – a daunting experience for a country boy.

“It was hard work, but I slept in a bungalow and got three feeds a day – and George had contacts with so many people in the industry, whether to do with the training or the stallions.”

He said he was now shining because of that O’Mealy polish.

“I would much rather have had it that way,” he insisted. “All the jockeys today say how hard they’ve got it. They wouldn’t know what hard is. There would be a public outcry if you treated apprentices like that today.

“I had to do what I did and the Pat Hylands and the Harry Whites probably did it harder. They’d probably call me soft and say that I had it easy.”

In those early years, Mertens conceded he had no real drive to succeed. He admitted taking the job, at 14, purely to get out of school. He attended Morwell and Sale technical schools and hated all but woodwork.

Until then his only brush with racing was winning 50 cents on 1973 Melbourne Cup winner Gala Supreme in a school sweep (and would later smile at the irony that he had now ridden a lot for Gala Supreme’s trainer Ray Hutchins and that they are good friends).

He said his ambition didn’t extend much beyond “going to a party and getting a girlfriend”.

“I didn’t really have any idea what I could get out of a riding career; there was no Sky Channel back then and you couldn’t pick up the races on the radio at Sale.

“I was focussed on other things and didn’t really get a kick out of racing. The dreams and goals just weren’t there.”

With the added distraction of his mother’s ill-health, Mertens threw in the towel in the early 1980s and took on “factory jobs” at the likes of the Loy Yang and Yallourn power stations in the Latrobe Valley.

He insisted he grew up a lot during that sabbatical.

He got married, they had a child and, with his mother’s health improving, he decided on a comeback.

The first person he rang was former Traralgon trainer Lloyd Timms, with whom he had finished his apprenticeship after three years with O’Mealy.

Timms only had a small team at Mornington at the time and advised him to link up with Allan Douch at Traralgon, who was flying with a team of about 20 horses at the time, and also ride the coattails of talented Sale trainer Ron Crawford.

It was good advice. He rode on the wave of Douch’s success and quickly established himself as a leading rider in Gippsland.

By 1988 he was ready to branch out into Perth, but fate dealt him a cruel blow when he broke his back and collarbone in a fall at Pakenham.

Mertens was told several times that he would not ride again, but each time just changed doctors.

Those 14 months out of the saddle were tough. He spent the first half of the time trying to come to grips with being told how lucky he was that he was not confined to a wheelchair.

“One minute I’m going to Perth to be the leading rider over there and the next minute I’m told I can’t ride – and people were telling me I was lucky. I couldn’t understand that.”

When during rehabilitation they began trying to teach him to do something else, Mertens became determined to prove the medics wrong.

Leaving behind a string of doctors, he finally got the answer he wanted in Hamilton, where a specialist said he could resume track riding within a month.

He was straight on the phone to Bruce Hill at Mornington and was soon helping with his 30-strong team.

Fittingly, his comeback ride was at Sale on New Year’s Day 1990, where he managed to ride a winner for Ray Douglas.

That was the real turning point in his career and Mertens said that, from there, he never looked back.